The magic of the short story seems outshined by the glitz of

the best-seller, soon-to-be-a-major-motion-picture, box-office smash complete

with new Hollywood cover shot of an actor’s photo-shopped face. I’m not

poo-pooing success—who wouldn’t want to see Matt Damon or Claire Danes playing

our characters?—just noting that stars falling from the sky and landing on a

book’s cover shouldn’t necessarily be the depth of our literary blind date.

Some of the stories that stick with us the most are those

finished in a dentist’s waiting room, a lunch break, or even waiting at the DMV

(unless you go to my DMV, then just break out War & Peace). Great fiction has heart. It has eyes that bore

into you, hands that shake you, teeth that bite. It leaves you with clips and

rushes of made up memories, fantasies, something dark, something chilling, and

something hopeful, something askew.

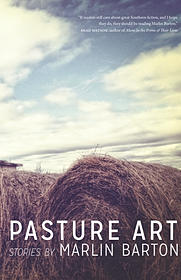

Marlin Barton’s latest short story collection, Pasture Art, is his finest work to date.

His work leaves lingering echoes that bring the reader back for another go. The

imagery is so lush that we know that river, field, and forest as a place from

our own past. Barton is a master at telling a story. His mastery shines in this

collection of shorts. His stories have heart. And, they have teeth.

I was given an opportunity to ask Barton a few questions

about Pasture Art.

When reading Pasture Art, it’s as though we’re in a

dinghy drifting on a river that winds through the collection. On the banks, one

plot of land cedes to the next and on each a different story. While this is a

collection of fictional stories, they feel real and this feeling is given life

by the fictional Tennahpush River. Does the river function for you as a character

or does its repeated appearance help you blur the lines between fiction and the

real world?

I suppose it’s both. The Tennahpush, and the Black Fork

River, which is also featured heavily in the collection, do feel a little like

characters to me, and they also blur the lines, in a personal way, between

fiction and reality. As for their being characters, I hope they come across as

living things: they move, they have depth, they have a history that’s older

than the people who live along their banks, and I hope they have a presence in

the book. For the husband in “Braided Leather” and “Haints at Noon,” the

Tennahpush offers aid in a possible escape from slavery, and in “Pasture Art,”

it holds a level of danger if you think about the fisherman who end up shooting

at the statues of deer at the top of the high bank.

Both rivers are fictional, but they are based on the

Tombigbee and the Black Warrior Rivers in Alabama. I grew up in a little

community called Forkland, which lies in the fork of the two rivers. I think it

was inevitable that rivers would flow through all my fiction, and when I

describe these rivers, I see in my mind’s eye the rivers that I grew up

swimming and fishing in, but I wanted to give them fictional names to remind

myself that I do need to create my own unique world for my characters. I have

to add that over the years I’ve submitted stories to the Black Warrior Review, with no luck. It does seem like a writer

who’s actually swam all the way across the Black Warrior, and it is a wide

river, ought to have some advantage in placing a story there.

Rivers play an

important role in your most recent novel, The

Cross Garden, and again throughout Pasture

Art. Scholars and critiques tend to relate a river to life but your rivers

are somewhat darker. Where does this influence come from?

Rivers are life-giving things, I suppose, but life also has

its darker side, which fiction must address. I’ve sometimes had my stories and

fictional vision, if that doesn’t sound too fancy a term, described in reviews

as “dark.” I don’t think of myself as a particularly “dark” kind of person; I

try to be hopeful, and I also attempt to reach a place of hope in my fiction,

but my stories and novels have often explored my characters’ capacity for evil,

which is a theme as old as literature. So I think I’m going about the business

of what I should be doing as a writer, and the rivers that run through my

stories are simply a part of that. In The

Cross Garden, for example, a murder by drowning has taken place, and I try

to suggest in the novel that the river itself holds the memory of that act,

just as it’s held in the memory of the main character Nathan.

Pasture Art features a number of stories from the female POV. What

attracts you to that POV? Is it easier to define the supporting male characters

from outside their POV influence?

I have often written from a female point of view. I’m not

sure why, and haven’t really thought about it all that much, to be honest. I’m

not the kind of writer who has notebooks and notebooks full of story ideas, so

when an idea comes to me that seems workable, I try to write it. Sometimes the

characters in those stories are male, sometimes female. And sometimes they are

of a different race. I think all writers have every right to write from a point

of view different from their own. How boring it would be to write only from a

middle-aged, white, male point of view.

Your remark about it maybe being easier to define a male

character from outside his point of view is an interesting one. In the novella

“Playing War,” the main character is female, and I realize just now that I had

to, of course, define her husband from her point of view. In many ways, that’s

what the novella is about. Their

marriage is deeply troubled, and Carrie spends most of the novella trying to

decide what kind of man her husband is, including if he’s capable of murder.

The way she sees and defines him changes, and I hope the way the reader sees

and defines him changes too. In fact, I hope the reader can sometimes see

Foster more clearly than Carrie is able, even though everything the reader sees

comes through her.

While all stories in Pasture Art stay with the reader long

after the book is closed, the collection’s final (and longest) work, “Playing

War,” is an intriguing, frightening page-turner. Was there ever a thought this

could be a novel?

Not really. I envisioned it as a novella from the start. I’d

thought it might run 100 manuscript pages or so, but it ended up running about

70 after I did a little cutting. I’ve never been a writer who experiments with

form really, but one of the things I wanted to do in this collection was to try

forms I’d never used before. So I wanted to give a novella a shot, and I

thought just maybe I had a story idea that could sustain the length required. I

also wanted to write a short, short, which was a real challenge. I think Brady

Udall’s short “The Wig,” which is one of the finest short, shorts I’ve ever

read, inspired me to try my hand at it. I’d also read a couple of volumes of

slave narratives taken down in the 1930s for the Federal Writers’ Project, and

it was a form that intrigued me. So while the short, short “Braided Leather” is

written from the husband’s point of view, I thought revisiting that story from

the wife’s point of view, and from a distance of many decades, might be a

revealing thing to do, and hopefully each story helps to enlarge the other.

Finally, there’s another story in the collection called “Midnight Shift” that’s

written from a multiple third-person point of view. I’d always written from

either third-person limited or from first person. While the story isn’t true

omniscient point of view, it still uses a point of view I’d never attempted

before.

If you take “Playing

War” and put it opposite “Braided Leather” you have a 50+ page story and a

one-page story, yet both have a powerful impact on the reader. When do you know

a story is complete?

Here’s the short answer: when it feels right. But that’s a

hard thing to know for certain. I suppose to give a kind of technical answer,

I’d have to say after the climactic moment has occurred and the conflict has

reached whatever resolution it’s going to reach, whether that’s a hopeful,

completely satisfying resolution, or not. Stories should not tie up too neatly.

Every little thread can’t always be accounted for. But the major issue at work

in the story must be addressed and resolved in some way, even if that resolution

is more implicit than explicit. The best stories work more by suggestion. They

end up giving you a sense of how the character’s life might be changed by

what’s just happened to them. By the way, I appreciate your compliment of the

two stories you mentioned, just as I appreciate greatly your reading the

collection so thoughtfully and wanting to ask me questions about it.

More information about Marlin Barton

Buy the book

***

ABOUT KEVIN WELCH

Kevin Welch holds the MFA in Creative Writing from Converse

College in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Currently, he works as an instructor at

Mt. Hood Community College, Portland, Oregon. He is working on his first novel,

Military Dreams.